The Swannanoa Gap Tunnel

Back in the day, the bookstore on the campus of UNC-Chapel Hill was a haven of mine. They dealt with the normal stuff – textbooks, merchandise imprinted with a ram, or a ram’s head, or a tarry heel, etc. - but they also carried specialty books, books that I love. Need a copy of Feynman’s book on quantum electrodynamics? They had several copies on hand. Don’t know how to solve a non-linear differential equation? There sits the 1962 book by Davis to help you out. A big part of my technical library was purchased there. In most cases, I didn’t know I needed a particular book until I saw it in the bookstore.

Kathy and I stopped by the bookstore in the summer of ‘22, and I was deeply disappointed. The specialty book section is no longer. In fact, apart from the textbook and merchandise portions of the store, it looks for all the world like a Barnes and Noble. Don’t get me wrong, I love Barnes and Noble. The problem is, if you want a specialty book, you have to order it. That means you need to know what you want first. Half the joy of the old bookstore was rummaging around, looking.

With no new math or science books to entertain me, I drifted over to the history section, and picked up a copy of The Heart of Confederate Appalachia: Western North Carolina in the Civil War, by John C. Inscoe and Gordon B. McKinney. I mentioned this in last year’s book review. I enjoyed the book, but it reminded me of a problem that our forefathers had that we generally do not have, and that is the problem of geography.

Today we can pop in an airplane and hours later disembark in the European city of our choice. We can see the summit of Mount Everest from above, looking out of the window of a jetliner. We know exactly where we are at any moment thanks to geostationary positioning satellites. Geography is not a problem for us.

It was for our forefathers. The slow development of the western part of North Carolina was due to geography. The mountains presented serious obstacles with respect to the building of roads and railroads. Gaps in the mountain became important, and two that were very important to the transportation needs of Asheville were the Hickory Nut Gap, to the southeast of the city, and the Swannanoa Gap, to the east of the city.

But even gaps in mountains sometimes presented problems. Steam locomotives of the period were not all that powerful, and at times it was necessary to tunnel under a hill rather than lay track over it. This was the case in the Swannanoa Gap.

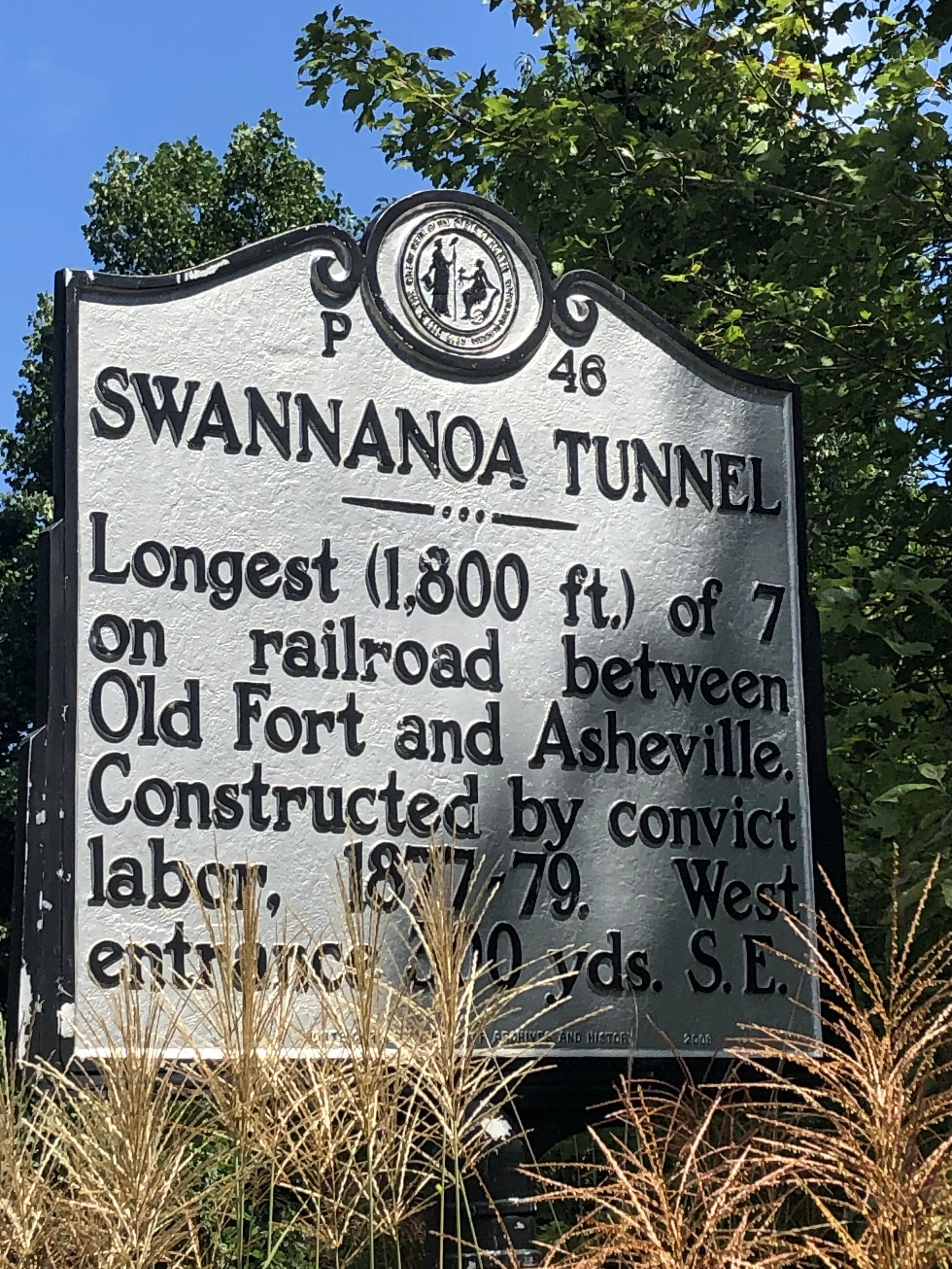

In 1877 the Western North Carolina Railroad began construction of the Swannanoa Gap Tunnel. This tunnel was one of seven constructed between Old Fort and Asheville. It has the distinction of being the longest hand-dug tunnel in the state (1,832 feet, or about 0.35 miles). Digging took place on both sides of the hill, and in March of 1879, the breakthrough occurred. Miraculously, the two tunnels lined up perfectly. It was another year and a half before the first train passed through the tunnel. A brief description of this tunnel can be found in this NCPedia article.

Most articles on the tunnel focus on two things: the tunnel was dug with prison labor, primarily African-Americans; and the digging was hastened by the use of nitroglycerin. This was one of the early uses of nitroglycerin in a construction project. A report to the NC Bureau of Labor Statistics noted that “the state’s convict labor crews were overwhelmingly dominated by black men who in most cases had only been convicted of minor infractions of the law.” Based on the old photographs I have seen, it does appear that the Swannanoa Gap Tunnel construction crew was composed primarily of African Americans. The use of nitroglycerin caused many cave-ins during construction. At least 300 people were killed as a result.

The tunnel was not easy to find. The historical marker P-46, shown above, is not located anywhere near the tunnel. The marker notes that one entrance to the tunnel is 300 yards away. This is true, but only if you are a crow. It certainly isn’t helpful information, as no trails near the marker lead to the tunnel. In part because of that confusing marker, we ended up on a nice hike to Kitsuma Peak that delayed our finding the tunnel by at least 30 minutes.

I doubt we would have found the tunnel without the assistance of a hiker we encountered on our way back from Kitsuma Peak. He had visited the tunnel the day before and gave us very good instructions. If you are interested, go north on Yates Avenue until it turns into Mill Creek Road, then continue north on Mill Creek Road. At the point where Mill Creek Road veers off to the left as a gravel road, a paved but inaccessible road to the right appears. This is the Point Lookout Trail, into the Pisgah National Forest. After hiking a bit you will be able to see the railroad off to the right, and eventually, the tunnel will appear if you keep looking over your shoulder.

In a way, it was a disappointing trip. I wanted to walk through the tunnel, but the land between the trail and the tunnel is privately owned, with signs suggesting strongly that you stay on the trail. Besides, to get down the hill to the tunnel, I would have had to trespass on one of the largest patches of kudzu I’ve ever seen. I can only imagine the number of rattlers and copperheads hidden there. Others have posted pictures and videos of the tunnel, but I discovered after our visit that these were taken with drones. My drone was at home. So I did not walk through the tunnel. It is just as well. By the time we hiked the wrong way to Kitsuma Peak, hiked back, and then hiked to the tunnel, I was getting tired.

On the bright side, Lucy enjoyed the hike tremendously. Kathy and I were so fatigued that we had to recover with dinner at Tupelo Honey.

Enjoy the pictures below. The photos were taken with my old iPhone. I did the best I could with the zoom function.

Here we are returning from our unplanned hike to Kitsuma peak.

Trailhead for the Point Lookout trail.

The trail will lead you to Old Fort.

I am posting all four photos of the tunnel, as I cannot tell which one is the best.